Back in the late 80s, film-maker Shane Meadows had aspirations of being a rock star – until he first saw his friend Gavin Clark perform at a mate’s house. “He was playing one of his songs on a guitar with two strings,” Meadows says, “and I just went, ‘Oh! Shit`cc , he’s ridiculously talented.’ He had this gentle voice with the power of a jumbo jet behind it. It was such a unique thing. I realised I was faking it. I saw what a frontman looked like.”

It is one of the tragedies of Clark’s life that success stubbornly eluded him. A big-hearted, fragile soul, Clark died in 2015 aged just 46 due to complications from alcoholism, leaving behind a slim but immaculate body of work. With groups Sunhouse and Clayhill, on solo records, and across a decades-long creative relationship soundtracking Meadows’ films, Clark’s signature music – emotionally sore blues and folk, where beauty met desolation – won a small but committed band of admirers. The great John Martyn called Clark “a peerless poet and songwriter”; collaborators included Sinead O’Connor, Warren Ellis, and UNKLE’s James Lavelle.

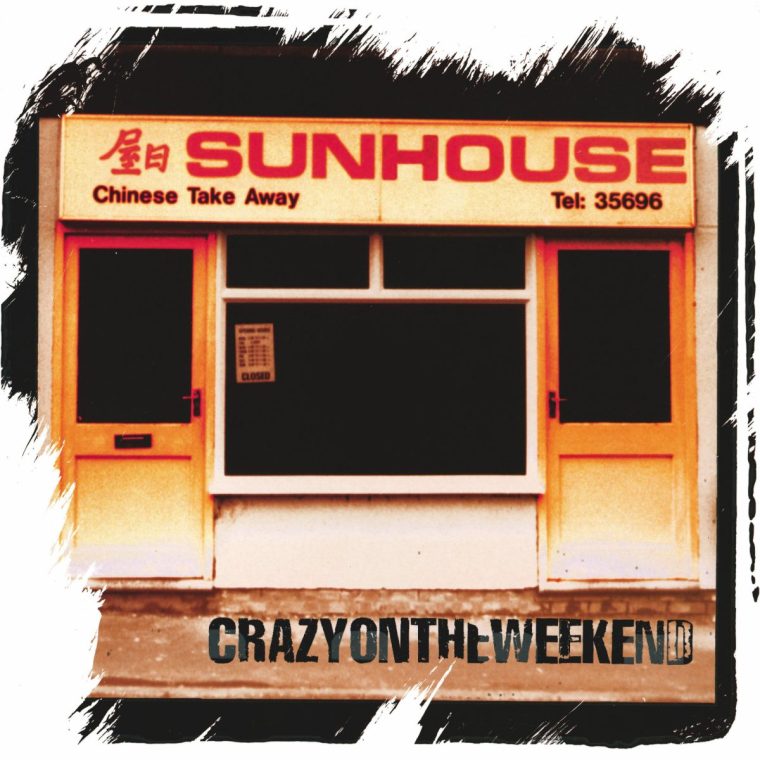

Clark is perhaps best known for his version of The Smith’s “Please Please Please Let Me Get What I Want” that soundtracks the unforgettable final scene of Meadows’ 2006 film This is England; Clark’s heavy, injured voice took the melancholic source material and plumbed new depths of sorrow. “There’s not many Smiths covers better than the original,” Meadows says. But Clark’s masterpiece is Sunhouse’s sole album, 98’s cult classic Crazy on the Weekend, which is getting its first ever reissue for Record Store Day through Rough Trade Records.

Clark and Meadows met at a house party in Manchester in 1989, when they were both living in the Midlands and working at Alton Towers (Clark at a food stall selling chips, Meadows painting clown faces). They bonded quickly amid the era’s rave scene. “Gavin had this aura around him. I looked up to him, he was like a big brother to me.” Meadows describes a fun, worldly and gifted individual who, even then, had insecurities. “I would say he didn’t have self-belief in his music. In a way, that stayed with him.” By this point, the wounds from the death of Clark’s father when he was 18 – prompting him to buy a guitar, and ease his pain with substances, too – were starting to manifest. “I realised how vulnerable that had made him.”

Both men saw their fortunes change with Meadows first film, 1996’s Small Time. When Meadows realised he couldn’t afford clearance for the soundtrack just before release, he introduced Clark to guitarist Paul Bacon and member of Burton band The Telescopes, bassist Rob Brooks. Within a week they created a new soundtrack, and inadvertently Sunhouse was born. “[Clark] was a lovely guy,” Brooks says. “A really talented songwriter, beautiful singer, but quite naive, from a musical perspective. And he was shy. The idea of performing for him was quite panic inducing.”

Impressed by what they heard on Small Time, record label Independiente signed Sunhouse. “It was clear from the off that Gavin was both a huge talent and a huge handful,” says Kill Your Friends author John Niven, who, back then, worked with Sunhouse as A&R for Independiente. “He was very confident in his opinion, sometimes when he wasn’t necessarily right. And he liked a drink. But guys that talented – it doesn’t come free very often. Something tends to be eating them up.”

Niven recalls a boisterous, good-time atmosphere as the band recorded Crazy on the Weekend with producer John Reynolds in Notting Hill in the summer of 1997. It was a creative time – and plenty of fun. “A lot of late nights. Gavin was hysterically funny. If you really made Gavin laugh, it was like a volcano erupting. He was capable of tremendous joy.”

Clark’s turmoil was channelled into his songs. From sparse balladry to heavy blues rock, Crazy on the Weekend unflinchingly dealt with depression, anxiety, chemical indulgence and grief – albeit with chinks of lights. “Lips” is a loving ode to his wife Judy. “Everything he wrote was so heartfelt and described in such a beautiful way,” Brooks says.

“His voice was just so raw and broken and emotional it was difficult sometimes,” Niven says. “It was almost too much to listen to. There’s so much pain. It was all we could do not to look at each other for fear of tears.”

The moment seemed set for Sunhouse in 1998. Reviews for Crazy on the Weekend had been glowing: Uncut magazine’s five-star review drew comparisons to Elvis Costello and Gram Parsons. The band played a well-attended show at Glastonbury in the New Bands Tent.

But the album just didn’t sell. Too late for the Britpop boom, it proved too early for a turn-of-the-century acoustic music revival that saw artists from Coldplay to David Gray sell bucketloads, and the Americana of Ryan Adams go mainstream. “We put out a rootsy-sounding record, and people just weren’t ready for it,” Niven says.

Clark took the album’s commercial failure badly. “It definitely hit him hard.” Meadows says. “You’re telling the truth from the bottom of your shoes. If that doesn’t sell many copies, and then you’re dropped from the label, that’s going to mess anybody up.” Within a year, Sunhouse fell apart. “We never argued as a band,” Brooks says. “But there was a lot of uncertainty with Gavin about whether he could continue. I guess he lost his way a little bit.”

Clark eventually regrouped with Clayhill, who – as was Clark’s fate – released three studio albums to acclaim, but no sales. Not even exposure from This is England brought a change of fortunes, and by 2007 Clark had withdrawn from music. He moved to Stoke with Judy and their young children, and got a job delivering pizzas. He didn’t even own a guitar. “I just thought, how is it possible someone with that ability hasn’t got a guitar and has no desire to write songs anymore, and is delivering pizzas?” Meadows says. “There’s honour in any manual work. But it crushed me.”

Meadows’ response was to make The Living Room, a documentary about Clark being coaxed back into live performance in real time via a show in his own front room. On the one hand it is a loving portrait of friendship and facing adversity. “There was no drinking,” Meadows says, “he was the best Gavin I’d seen for a really long time.” But it was a tough watch. In debt, regretful, and wracked with anxiety about performing, Clark wilted under the pressure of playing for family and friends – hands trembling, voice cracking. Meadows says the intimacy of the occasion “was maybe the worst idea. It probably would have been easier for him to do it at Wembley.” But Clark overcame his stage fright, and went on to tour by himself and as a vocalist with UNKLE. In 2014, he released a solo album, Beautiful Skeletons.

But his demons returned. “I don’t know at which point, exactly,” Meadows says. “I’ll be honest, I feel a responsibility. By wanting so badly for that person to have their voice heard, I’ve wondered over the years if him going back on the road was maybe where he did start to drink again.”

Meadows used tracks from what turned out to be Clark’s posthumous album Evangelist in 2015 TV series This is England ‘90. Clark attended the preview screening – the last time Meadows saw him.

“I knew he was poorly, but it was a massive shock,” Meadows says. “As a friend, I miss him the most. Because he was the least judgmental person I’ve ever met. The pain he felt in his life, he never turned that on other people. He used it to see it in other people and try to help them. And that’s rare as f**k, man.”

Brooks had lost contact with Clark after Sunhouse’s split: “I will always remember Gavin with love. For a while, we were brothers.”

Crazy on the Weekend’s reissue offers a chance for Clark to get some overdue acknowledgement. As Meadows puts it: “It’s like Nick Drake. This person was never appreciated in their own lifetime.”

The vinyl reissue of Sunhouse’s ‘Crazy on The Weekend’ is out 12 April via Rough Trade Records