[ad_1]

An ingenious puzzle-platformer that takes players from a children’s book and out into the wider world around it.

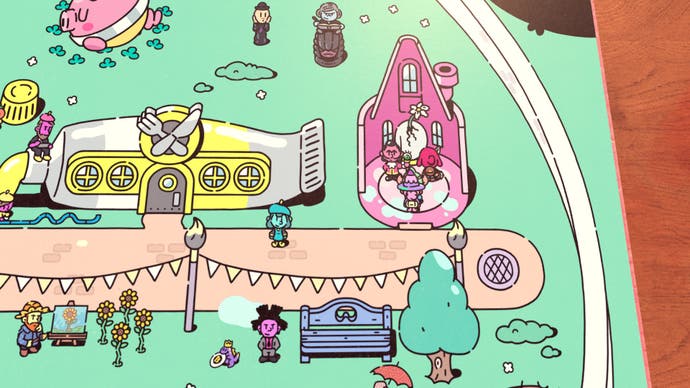

It’s probably strange to accuse a game like The Plucky Squire of realism. This is a game in which a heroic character from a children’s fantasy book can leap from the pages and rove around the bedroom desk on which the book was being read. It’s a game in which you can move back and forth, from 2D illustration to chunky, squishy 3D in the name of adventure.

But that desk you end up on. It’s something else. It’s something I recognise. And it may be the thing that really lifts this game into the realm of magic. The book is lovely stuff, obviously, all bustling towns and sloshing swamps, all mysterious forests and towering mountains. But the desk is its own magical space, where the shifting architecture is built from old wooden blocks and pots of ink, where a bridge may be made out of a ruler and Post-It blocks might lean together to form a rudimentary house.

It’s a reminder that childhood is often a time of looking at things up close and for prolonged periods. Wood grain. The scuffed backs of playing cards. The domestic world has the power to slightly hypnotise when you’re a kid, I think. It has the power to present endless cascading possibilities, to merge day and day-dream. The Plucky Squire captures this beautifully.

In turn this explains why a game made of such simple, even basic pieces – combat, a little platforming, regular puzzles – comes together to create something singular. By building itself from the same things a child’s imaginative world is made from, it transforms a nicely built game into something ingenious and quietly moving.

It’s all so elegant too. The Plucky Squire is the local hero of a fantasy world, who discovers, when he’s battling the evil wizard Humgrump, that he’s actually a character in a book. He discovers this by being flung out of the pages and into a weird close-up world of paperclips and pencil sharpeners and jotter pads where someone’s been doodling the Squire’s face.

What follows is an adventure to stop the wizard from rewriting the book, by moving through the fantasy world within its pages, shifting from top-down battling, say, to side-on platforming, from colourful towns to shadowy caves, picking up a bunch of pals as you go, and then sequences in which you must move outside the book, to scrabble over that 3D world of the desktop, occasionally warping into 2D sections when there’s a handy child’s drawing pinned to a wall or pasted onto a bit of cardboard.

Combat, puzzling and platforming all become fresh again when you have this sense of moving between worlds. In the book there’s a lot of fun to be had with violent actions that shake the pages, or when a boulder, drawn in ink, reaches the edge of a page and turns into a real tumbling rock. Puzzles often hinge on making new sentences from the narration that lays around you, picking up the right words to open a locked door, say, or freeze a lake so you can cross it.

Even when you’re a 2D drawing, it’s pleasantly physical too. In platforming sections you must pick up blocks to weight down switches – hardly revolutionary, but then sometimes you get to take those 2D blocks out into the 3D world, and the magic is so innate that I was always delighted. Combat, meanwhile, is simple but nicely kinetic. Enemies squish and pop under your attacks, which are dealt with a sword that I only recently noticed is also a pen nib.

Moving between worlds is neatly handled too. This is a puzzle game rather than a sandbox, so there are set spots within the book where you can move from the 2D to 3D realm, and you’re generally dispatched to collect a new item that will prove useful back in the book itself. Alongside platforming gauntlets out there on the desk, you can also collect gadgets that will allow you to manipulate the book itself in interesting ways. I don’t want to spoil too much, but the simplest of these allows you to turn the pages, meaning you can drop back into earlier sections of the narrative and emerge with useful things.

It sounds complex, but it’s all used for simple enough puzzles. This is a game for children, after all, as well as being a game for adults that happens to be about childhood. It’s also a game in which the conceits stand out more than the individual puzzles. I loved a section in which I left the book and travelled up through the rooms of a doll’s house, because it was fascinating to explore a doll’s house that reminded me so much of the doll’s house my daughter had. The individual puzzles were fine, but the framing was phenomenal.

The same goes for a great moment in the book where the Squire arrives at the main town, Artia, and finds it filled with famous artists from our world. You get to take on a quest from Magritte, which is not a sentence I thought I would be typing. The quest is a bit fetchy, but again, it doesn’t matter as much as the fact that it’s Magritte who gives it to you. I would do anything for that guy!

There are moments, inevitably, where the magic falters just a little. The reuse of certain puzzle ideas can lead to sequences where the adventure gently flags. The game is a victim of its own delights, perhaps: there’s so much invention here that the repetition stands out all the more. There’s also a handful of pacing issues, not least that the game has a habit of interrupting its own flow to explain things. I think this comes from the game having to balance two audiences – kids and adults – but there are still a few too many unskippable conversations when even younger players will want to just get on with things.

These, and the odd fiddly mini-game, which thankfully can be skipped, are minor caveats though, given the glorious stuff that The Plucky Squire brings its players. This is a series of simple game ideas touched with magic and memory. It’s a game about the inspiration that the right piece of art can bring when encountered at the right moment in childhood, and I suspect it will go on to inspire the people who play it.

The Plucky Squire review code was supplied by the publisher.

[ad_2]

READ SOURCE