Believe it or not, Ethiopians do know it’s Christmas.

True, they celebrate it two weeks later than we do, but Ethiopia adopted Christianity long before most people on our own island.

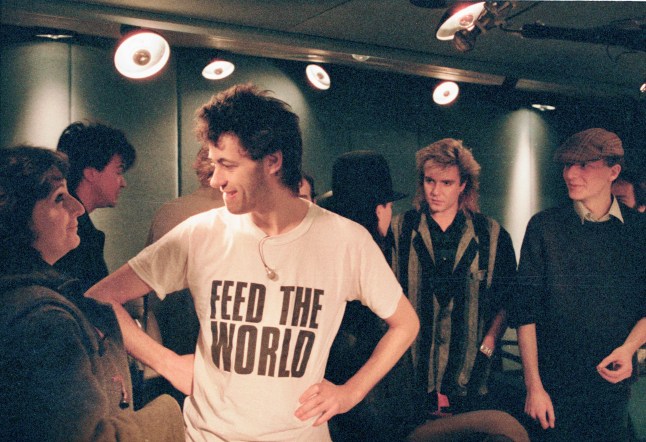

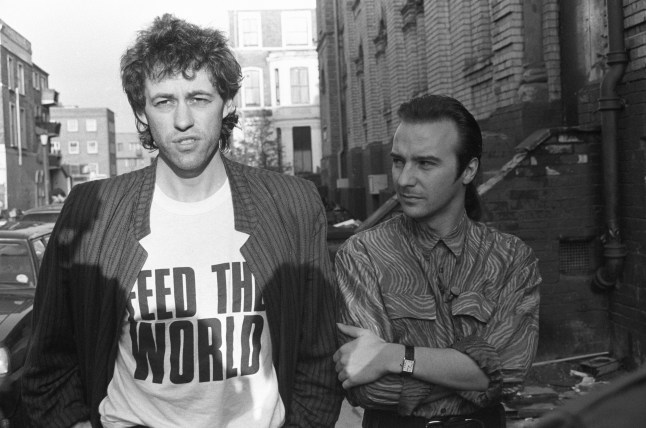

Of course, I’m referencing Bob Geldof and Midge Ure’s ‘classic’ Do They Know It’s Christmas? – a song written in 1984 in response to the Ethiopian famine and originally performed by a wide range of celebrities, including George Michael, Sting, Bono, Duran Duran, and Bananarama.

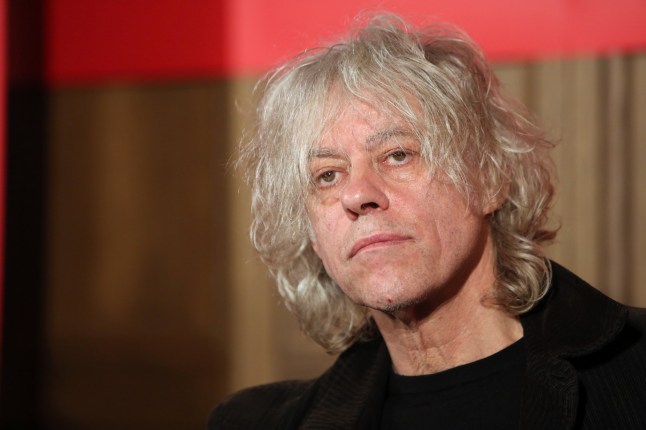

And now the British public has been forced to suffer the 40th anniversary re-release. But – four decades later – I believe we need to consign this record to history.

For anyone unaware, the song was written in the wake of shocking BBC news reports that showed severely malnourished victims of an awful famine in Ethiopia. Irish singer-songwriter Bob Geldof wanted to do something to end the suffering.

The song was used as a charity fundraiser for famine relief – and it raised a lot of money. It then became a model for how charities would run these types of appeals in the years ahead.

But there were problems.

Even at the time, Do They Know It’s Christmas? was crass.

The more absurd lyrics – portraying a country full of mountains and lakes as one ‘where nothing ever grows, no rain nor rivers flow’ – have thankfully been removed. But the overall picture remains: an Africa of helpless, starving children in desperate need of Europe’s generosity.

Forty years ago, Band Aid’s simplistic message seemed to erase all political complexity from the Ethiopian famine. In reality, the famine was not a simple natural disaster, but a drought that was used and exacerbated by a brutal government to destroy rebel fighters challenging its authority.

The failure to recognise this has real consequences, as there have been accusations that money was channelled through authorities that bought weapons instead of providing famine relief. But the problems didn’t end there.

There exists a phenomenon called the ‘Live Aid Legacy’. Named after the charity concert in 1985 – just one year after Band Aid’s Do They Know It’s Christmas – it essentially casts the UK public in the role of ‘powerful giver’, and the African public as ‘grateful receiver’.

As time went by, we saw more – rather than less – poverty on our screens, as charities used Band Aid as a model for how to raise money. This oversaturation meant that many people developed a hopelessness when it came to eradicating global poverty, as there were seemingly endless appeals that never felt like it made the situation any better.

Feeling helpless, many people simply turned away from the problem. They began to believe that, no matter what they did, things would never improve.

As a result, from the late 2000s, public engagement on the issue of global poverty started falling.

In essence, we felt (and continue to feel) lied to. But the problem of poverty can be solved – just not by charity alone.

Poverty in Africa – as it is here – is deeply political. There is more than enough food in the world to feed everyone. So why are so many still hungry? Because we have a society that allows some to grab far too much, while others have nothing.

Unfortunately, some countries suffering from chronic hunger are prioritising the export of cheap food to richer parts of the world, often on the terms dictated by western supermarkets.

Take Haiti, one of the hungriest countries in the world, which was once nearly self-sufficient in rice production under 20 years ago.

Deeply unhelpful trade rules forced on Haiti by international organisations destroyed the country’s rice industry. Now it imports the vast majority of its rice from the US, with traditional rice-farming areas of Haiti having some of the highest concentrations of malnutrition.

Haiti exports food crops – like cacao and coffee – but farmers don’t often get anything near a fair price for these products.

It seems to me that the Band Aid model obscures these unfair relationships, suggesting instead that charity will solve the problem. At a certain point, what could once be overlooked as a clumsy – if well-intentioned – effort to help people becomes simply offensive.

And Bob Geldof appears to remain tone deaf to criticism, even as more and more charity workers – and indeed musicians – urge him to stop promoting this vision of the world. A world which is, at its core, racist.

Geldof defends the song, claiming it ‘has kept millions of people alive’. It’s true, the song has raised plenty of cash – in fact, within a year of its release, the song raised £8 million for famine relief in Ethiopia.

But if that’s done so by extending an untrue, unhelpful, and offensive picture of the African continent, then it won’t help to bring about a world without hunger.

Giving to charity is certainly not a bad thing, but it’s far from the whole solution. So as well as donating, we need to take action to challenge our own government’s role in pushing policies that make the world a less fair place.

Our government could demand that big agricultural corporations operating overseas pay the farmers they rely on properly – not to mention paying their taxes. But they won’t do that unless we demand it.

If we succeed, we’ll quickly get to a point where charity is no longer needed.

In my view, Bob Geldof can no longer pretend that re-releasing his outdated song is doing anything more than getting him air time.

If you enjoy a bit of nostalgia, feel free to dig out your old Band Aid record. But don’t fuel the sales of a song that is simply reinforcing tired and unhelpful stereotypes.

At the end of the day, Geldof needs to stop re-releasing Do They Know It’s Christmas?

It is patronising and offensive to many people in and from the African continent. And it is a dangerous distraction from the real task of making the world a better place.

Do you have a story you’d like to share? Get in touch by emailing James.Besanvalle@metro.co.uk.

Share your views in the comments below.

MORE: This under-the-radar BBC drama is the best thing I’ve seen this year

MORE: John Boyega’s cousin faces deportation over £1,900,000 fraud at ‘cult church’

MORE: I’ve seen the new Jaguar up close – it is chunky and bulky, but what’s wrong with that?