When I left university in 2015 armed with a music degree and a youthful spirit, I remember talking to a friend about what clearly seemed like the dream job: being a playlist curator at Spotify. At the time, we seemed to have reached peak playlist culture. Spotify still felt novel and cool, and it was flooded with vibes and moods and themes that also felt novel and cool. How exciting, how creative, to be able to sit in an office listening to music all day and categorising your favourite songs! It sounded like a professional version of what I already did all the time just for fun.

Over the decade since, Spotify has added gimmicks and marketing campaigns; expanded its playlist offering; increased its reliance on algorithm rather than those “lucky” people sitting in offices picking out songs. It is, for many of its almost 700 million users, now virtually synonymous with music itself. But at the same time, for me and many others, it’s no longer the musical utopia it once seemed. Little by little, through reports into royalty rates and label deals, many of us have begun to realise that Spotify isn’t only the “celestial jukebox” it appeared to be, but another behemothic tech company mining data and weaponising culture for profit.

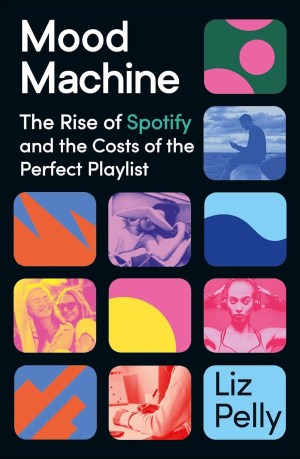

Mood Machine, the new book by journalist Liz Pelly, shows us all this and more. It’s an excoriating look at the history of a company that germinated as a way to circumvent the threat of online piracy and which has steadily flattened music into a homogenous mass of streamable vibes. Streaming now accounts for 84 per cent of recorded music revenue and it’s difficult to imagine our lives without it. Though Pelly’s book has plenty of dirt on Spotify’s familiar bad press – namely its terrible royalty rates – it also uniquely poses an idea much more philosophical: that Spotify, or “Spotify culture”, has contributed to a fundamental change in the purpose, function and meaning of music.

Spotify’s two founders, Daniel Ek and Martin Lorentzon, were, Pelly says, “two advertising men capitalising on the music industry’s weak status in their home country” – in Sweden in the early 2000s, piracy was rife; if people were going to share music online anyway, why not monetise it? Originally their service ran on advertising revenue, then it introduced the “premium” monthly subscription model.

A few years later, as they applied for their patent in the US, they were still saying the platform would circulate “any kind of digital content, such as music, video, digital films or images” – much like Elon Musk’s original vision for X, formerly Twitter, as an “everything app”. In other words, Spotify wasn’t originally really about the music, or, at least, music wasn’t essential – rather, it was fodder around which to build a product.

It soon evolved into more than just “Google for music”, as Ek once described it. And it was after the novelty of its search-engine capabilities wore off that I fell out of love with it myself. Rather than it being my own library, I felt increasingly bombarded by Spotify’s choices, by feelings and circumstances I didn’t know applied to me. “Chillin’ on a Dirt Road”? “Farmer’s Market”? “POLLEN”? Sure, I guess. But where was my collection, my taste, my love of actual music, in all of this?

Reading Mood Machine helped to contextualise why I suddenly felt so disconnected from something I had loved my whole life. Ironically, beginning in the 2010s and continuing to this day, Spotify is almost entirely set up to cater to the individual, using the algorithm to build a musical world around your personality, feelings and habits (in 2018 the company applied for a patent for emotion recognition technology, in which AI software would detect how you were feeling from an Amazon-Alexa-style voice prompt and recommend music accordingly; it was granted in 2021).

But these digital mixtapes were nothing like the iPod playlists we made or CDs we burned. They were consciously, deliberately about “music as a background experience”, as one of Pelly’s sources tells her. Far from reflecting our actual emotional worlds, they were vague, vibey, nothingy – “frictionless”, as Pelly puts it – dedicated to the task of smoothing the edges of life, rather than capturing sharpness in the way that only music can.

This had a huge impact on music makers too, of course – and Mood Machine lays out in grim detail exactly how the playlistification of the industry has changed what’s being made. Being picked by Spotify selectors, and later the algorithm, for big-hitting playlists has replaced the well-worn artist’s struggle to get played on the radio – but to frame it as directly analogous would be inaccurate; in fact, it’s much less transparent and fair.

Perhaps one of Pelly’s most chilling revelations is about “PFC” – “perfect fit content” – music created solely for the purpose of filling mood or occasion playlists, written by composers for libraries that are easier and cheaper to license than traditional label-owned music, and then made to look like it’s by “real” artists.

Pelly explains that the artist listed on Spotify as Ekfat, for example, whose songs have appeared on editorial playlists like “Lofi House” and “Chill Instrumental Beats” and have millions of streams – and whose bio stipulates that Ekfat is a “classically trained Icelandic beatmaker who graduated from the Reykjavik ‘music conservatory’ and released music only on limited-edition cassettes until 2019” – in fact comprises “three Swedish guys” who make music under different monikers and constellations.

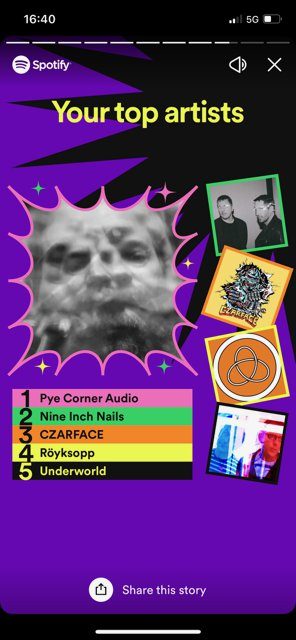

introduced marketing gimmicks such as Spotify Wrapped

Playlist curators, Pelly writes, were encouraged to include as much PFC as possible: not only was it cheaper for Spotify, but the music was inoffensive and repeatable, encouraging limitless plays, more minutes listened, and helping the platform in its quest to usurp its main competitor: silence.

Music has always adapted to social change and technology. Pelly lists a few examples of this herself: the invention of the phonograph determined that a pop song should be around three minutes long, which persists today; vinyl records inspired classical instrumentalists to use more vibrato.

We can look even further back to understand just how porous music is: during the Reformation in the 16th century there were seismic changes in music; choral church music had previously been written to evoke deep feelings in the listeners through ornate complexity and polyphony, but Martin Luther wanted everyone to be able to reap the spiritual benefits and so encouraged the singing of simple, congregational hymns with words in English rather than Latin. As literacy increased among the working classes in the 19th century, folk music – previously a solely oral tradition – started to decline in favour of written-down lyrics.

Spotify’s influence on the musical landscape is, perhaps, not much different – but that change and adaptation is natural doesn’t make it any less scary in context. This particular musical shift is inextricable from the rise of social media, the “attention economy”, globalisation and the continued blurring of lines between products and art. It is representative of the enormous power wielded by corporations, who – if we’re using historical analogies – function rather like the noble patrons who once commissioned music to be performed in their courts, except now they dictate what is performed to much of the world.

Pelly explains that “the very concept of music streaming was designed for the benefit of extremely popular, major label music” – while making playlist-friendly, streamable slush certainly fuels ambition to an extent, it’s also true that not every musician wants to be a pop star. Just as the 78rpm phonograph would not have accommodated “Bohemian Rhapsody”, and just as a folk melody loses a part of itself as soon as it’s transcribed, so the Spotify size does not fit all.

But perhaps most scary is how music’s function in our own lives has changed – how many of us who have grown up with streaming have felt that deep, granular experience of listening to records slipping through our fingers.

Worst of all, we’re not powerless to stop it – CDs still exist, our brains are still perfectly capable of engaging uninterrupted with a full-length album – it’s just that it’s inarguably convenient to have all music on tap for a mere £9.99 a month and to dabble as your impulse dictates, just as it’s inarguably convenient to have a pack of biros delivered to your door by Amazon on the day you order them, or to order a mezze platter and a bowl of Vietnamese pho to your sofa from Deliveroo because you and your partner had different cravings that day, or to let Netflix auto-play 15 hours of Love is Blind because it comforts your frazzled brain.

It is easy to listen to music on the move, as we cook, as we drive. It is smoothing, soothing. And Spotify has achieved the ultimate capitalist feat of solving the problem it created: when we are overwhelmed by the infinite choice of what to listen to, it gently guides our hand.

Mood Machine reminds us that music is not always meant to be frictionless – and that if something seems too good to be true, it probably means someone else is losing. Among these losses are, of course, artists’ incomes, as well as the flattening of the most beautiful and mysterious art into a shiny interface curated by robots. But the greatest loss of all is for us, the listeners, drawn in by what Spotify sells as our own reflection, rendered in sound – only to find a facsimile of both ourselves and the music we love so much, and not knowing where else to look.

‘Mood Machine’ by Liz Pelly (Hodder & Stoughton, £22) is out now