A few years ago, a music producer noticed that a track he had worked on 20 years previously had been streamed millions of times. It was strange, he thought, because he hadn’t received any royalties from the song.

So he contacted his label, who told him they hadn’t been in touch because they did not have his current address. “If I owed money to a major record label, trust me, they could find me very quickly,” the producer, who asked to remain anonymous, says now.

It took two years of “prodding” before the label paid the producer the £20,000 he was owed, as well as an even higher sum to the track’s artist, who hadn’t received their royalties either. “These are people’s lives,” the producer says. “And I’d love to say I am an exception to the rule, but this is a regular occurrence.”

This kind of story is all too familiar to Annabella Coldrick, CEO of the Music Managers Forum, which advocates on behalf of its manager members for a fairer industry. “There’s a lot of that,” she says, describing the above as just one example of how there is “so little transparency in the market”.

On the face of it, the music industry is thriving, with record sales reaching an all-time high in 2024. But not everyone is seeing a fair share of these profits.

“The top of the industry is absolutely booming,” explains Coldrick. “The world’s biggest artists are earning more than ever before.” Yet there is an increasingly prevalent “squeezed middle”, such as pop star Kate Nash or indie group Sports Team, who have recently spoken out about the financial realities of being a musician.

Coldrick says this is because many mid-level artists are signed to major label record deals. Even if, unlike the producer above, they’re not having to track down their own royalties, “they’re probably not seeing much, if any, of their streaming income, because they will be paying off the recoupment and the recording from their advances, often out of an appallingly low royalty rate”.

The economics of music-making can seem complicated. But in essence, a traditional major label record deal (that’s one with Universal Music Group, Warner Chappell, Sony or one of their subsidiaries) works like this: a label pays an advance to an artist to cover the cost of making a record. They also agree on a royalty rate – which is typically 80 per cent of earnings to the label and 20 per cent to the artist. But before the artist sees any of those royalties, they first must pay off their advance – which might be hundreds of thousands of pounds. This is known as recoupment.

An artist recoups only with their 20 per cent. “So it takes a really long time to become recouped and start earning money,” Coldrick explains. In the meantime, the label may already be profiting from the artist’s music.

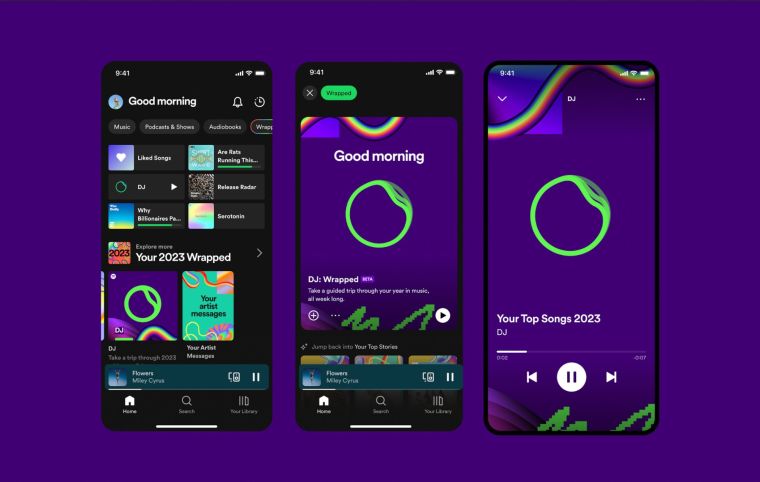

If that sounds unfair, it gets worse. The introduction of streaming made the picture even murkier. Spotify, which launched in the UK in 2009, keeps approximately a third of its revenue, meaning this money never gets anywhere near artists. The company’s annual “Loud and Clear” report, which shows how much artists are making on the platform, was published earlier this week. It is full of big numbers that might give the impression artists are being paid well – Spotify paid out $10bn in royalties in 2024. But the reality of how that money is distributed is complex.

Another industry insider, who asked to remain anonymous, explains: “At the advent of streaming, the major record labels interpreted terms from contracts” and applied them to the new format, “without consulting with music makers”. The result is that many artists continue to be tied to 80/20 royalty rates for streaming – but the format is nothing like the “sale” that 80/20 split represents. That ratio is based on a system where labels worked on distribution, marketing and publicity to make sure albums got into shops and the hands of fans. Today, algorithmic streaming means a Spotify user might listen to a track simply because the algorithm has pushed it to them, which requires little to no input – let alone 80 per cent’s worth – from the label itself.

That’s not all. Contract terms written for pressing vinyl and CDs and shipping them around the world were “interpreted” for the streaming era too. Thus contracts sometimes still include charges for packaging deductions and breakage despite the fact that streaming accounts for over 85 per cent of all music consumption, and distributing an album digitally costs just a fraction of the physical comparison. “It’s completely immoral,” the insider says.

All this means the majors are making more and more – Universal CEO Lucian Grainge earned a hefty $150m in 2023 – while artists are missing out. “We’re seeing the return of a heyday for the major labels,” the insider adds, referring to the pre-streaming age of the late 1990s and early 2000s, before digitisation meant record sales slumped, and piracy threatened the industry. “We’re seeing them become gatekeepers again.”

The majors have themselves acknowledged this boom: “The good news is that our margins are way better when compared to the last great era of profit 20 years ago,” Rob Stringer, CEO of Sony Music Entertainment, said in 2019.

“The record business was pretty bad before, when it was owned by individuals who were just trying to get rich,” says Tom Gray, chair of the Ivors Academy, a professional association for songwriters and composers. “But since they’ve become public companies, that maniacal drive for profits has become the thing: market share, consolidation, growth. It hasn’t got much to do with music. It just has to do with asset wealth, pension funds.”

But artists are fighting back. Earlier this year the Irish rock group The Cranberries sued their label Island Records (which is part of Universal), alleging millions in unpaid royalties. This kind of case has precedent: in 2022 the electronic musician Four Tet won a feud with his label, the independent Domino Records, over streaming and download royalties, with Domino agreeing to honour a 50 per cent rate. The case shows it is not just the majors who run on these unfair terms – indies are culpable too.

Additional complexities make the business of royalties even trickier. For example, when the major rights-holders first agreed to license their catalogues to streaming platforms, some agreed “most favoured nation clauses”, says Gray, which stipulate that the streaming service cannot give them a worse deal or pay them less than any of the other major labels. But when signing a record deal, an artist might be agreeing to lower rates than if they’d gone with a competitor, and because “all of this will be covered by an NDA [non-disclosure agreement]”, Gray adds, an artist and their team has no way of knowing.

What’s more, last year Spotify demonetised all tracks with fewer than 1,000 annual streams in a scheme thought up by Universal. The rationale according to Spotify is that this will help stop small payments getting “lost in the system” of the record labels, but in reality it still benefits the labels rather than DIY and independent musicians. Streaming royalties are paid directly to rights holders (not artists) according to the percentage they own of all the music streamed that month. So under this scheme, earnings are taken from artists at the bottom of the scale and filtered up to the top of the system, where artists are more likely to be on major labels – so the majors win, yet again.

They’re trying to call that the ‘artist-centric model’,” says Gray. “No one spoke to any of the artist groups about it. It’s the most hilarious piece of gaslighting.”

“It’s a reverse Robin Hood,” says the anonymous insider, adding that the change “has made accounting completely opaque”. An artist with fewer than 1,000 streams now isn’t given information on their listeners. “All you can see, as an artist, is: I’m below this threshold, so I’m being demonetised.”

This move was possible because of the power the majors hold, in particular Universal, which owns 36.2 per cent of the recorded music market. This figure is likely to grow further: the multinational hopes to acquire the Downtown Group, a leading music services company. There is still a chance the deal will be blocked, but all signs are pointing towards more and more market consolidation, which Gray says “is only going to give them more power in those licensing deals”.

The anonymous source adds that because of this consolidation, Universal has the power to “turn around to Spotify and say, ‘We’re going to pull our catalogue off unless you give us what we want’”. The demonetisation scheme may only be the beginning.

The i Paper contacted Universal, Warner and Sony but the labels declined to comment, deferring instead to the British Phonographic Industry (BPI), the trade association that represents the interests of record labels.

The BPI would not comment on specific matters, but CEO Jo Twist said: “Streaming has helped to give artists more choice than ever in how they release their music, and many more are achieving meaningful success and increased earnings across different income streams thanks to the essential support of record labels in amplifying their talent and helping them to realise their creative potential.

“With the explosion in the number of artists globally all looking to cut through, popularity with fans remains the key determinant of artist success and earnings, and being with a label gives them the best chance of achieving that – which is why so many artists choose to release their music through them.”

“We do think there is a role for major labels,” says Coldrick, who works on the cross-organisational Council of Music Makers to lobby for change. “It’s just: is it fair? Is it transparent?”

Coldrick is calling for regulation on artist payments and contract negotiation, arguing for “a floor, like there is a minimum wage”. Otherwise it all comes down to “how much negotiating power you have. And how much negotiating power do most 18-year-olds have when they sign a record deal? Not much. They’re pretty starstruck. They will put their pen to anything, and then spend the rest of their careers regretting it because there’s no minimum standards.”

Gray is also lobbying the government for change. “It’s weird that what is basically a data and payment industry doesn’t have any regulations,” he says, concluding that the major labels “are eating [the music business] alive, for no reason other than they assume there will be other children waiting in the wings who want to dash their dreams on the rocks of this system”.