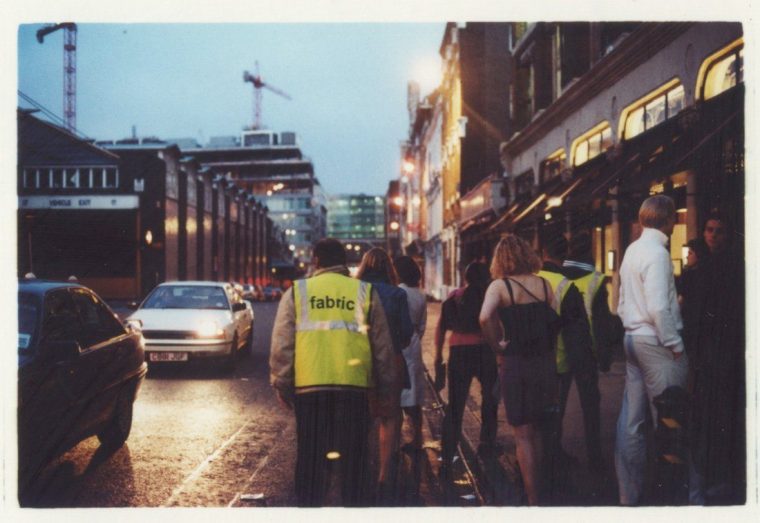

Slipping out of Farringdon’s shiny new Elizabeth Line station, and heading around a couple of corners, I’m swept up in a Proustian rush, as the Victorian sight of Smithfield Market looms over me in the evening twilight.

Some 15 years ago, I used to see this sight in the twilight at the other end of the day, as part of a dishevelled, sweaty mass shuffling out through the metallic double doors of Fabric nightclub and on to Charterhouse St, confronted with a rising sun and the amused or bemused looks of the market traders gearing up for opening.

In the superclub era – Cream, Ministry of Sound and Godskitchen – Fabric was where I wanted to be. It felt more intimate and real, an underground club with underground sensibilities. This former cold storage unit next to a literal meat market became a dark mecca for many a reveller.

This evening, I once again descend the many staircases into Room 1, the belly of Fabric, 25 years after it first opened. While millennials like me, and younger Gen-Xers, may immediately think 25 years ago was 1975, to help us to face up to the fact that we are now the adults in the room, I must tell you that it was 1999.

“It’s mental looking back – it was coming to the end of my youth in 1999, it felt like the end of a phase of dance music,” says writer and DJ/music promoter Joe Muggs, who has been immersed in the dance scene for even longer than Fabric has as a Fabric regular and expert chronicler of UK dance music. “But Fabric is about something longer and deeper, which didn’t care about it being the end of the 90s.”

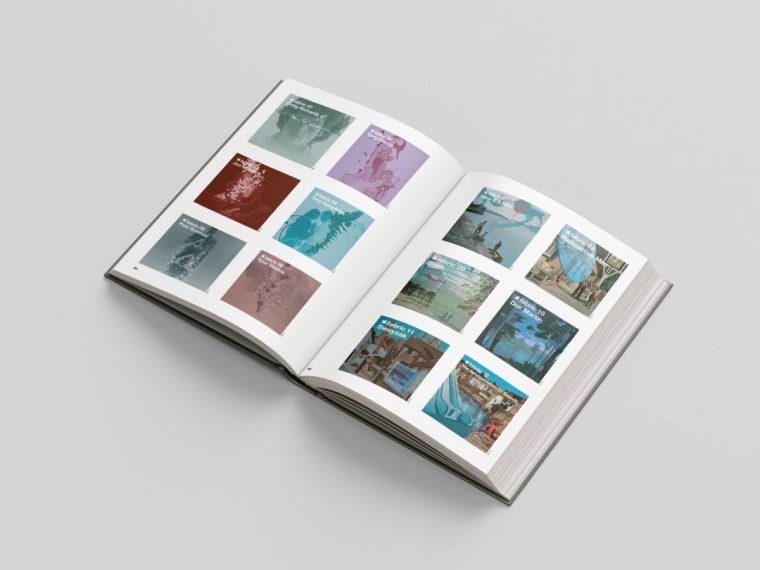

Muggs has written Fabric the Book, in collaboration with the club, to mark its silver anniversary. The sleek tome features rare photography, archival images, old flyers, and iconic club artwork. It comes in standard edition, special edition, and super deluxe which includes an LP, flyers, and a slip mat… the VIP section, if you will.

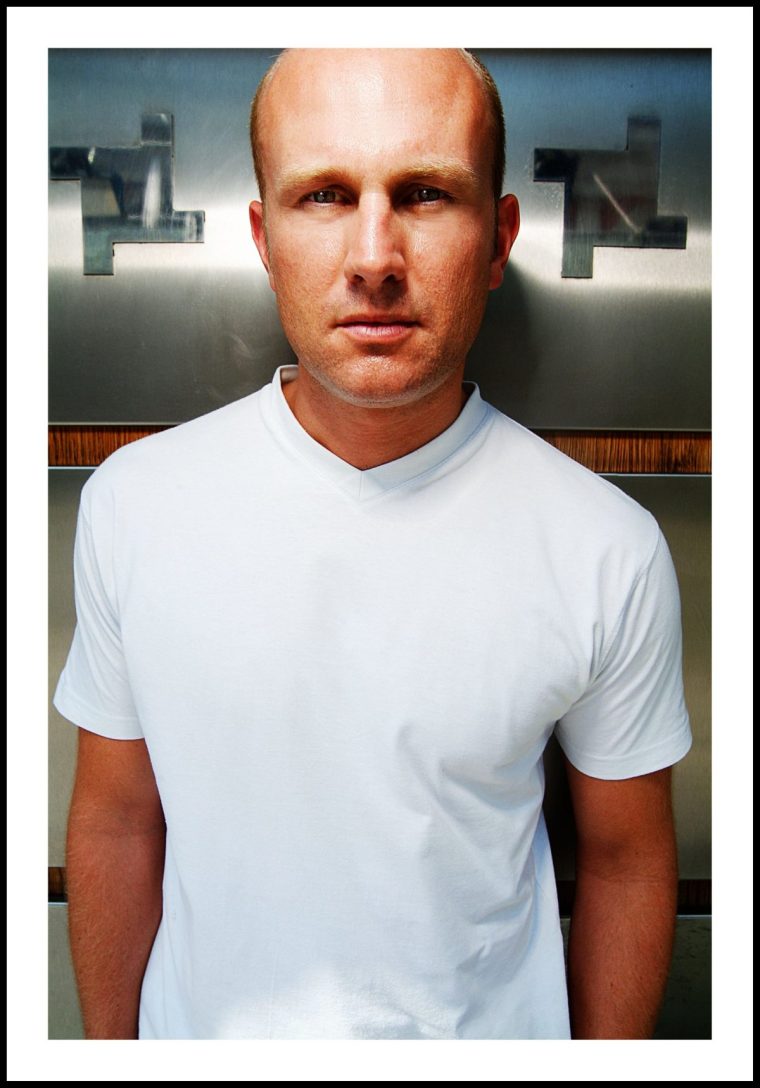

I am also joined by Fabric co-founder Cameron Leslie. I ask him if it feels like 25 years. “Yes, it does!” he says with a laugh. “Part of doing the book is going on that strange journey of digging through physical archives, and the archives of your own and other people’s brains. When you do that, time bends very strangely. Some things feel like an absolute lifetime ago, and other things you can’t believe it’s been so long.”

Fabric opened at the end of a decade that had seen dance music and clubbing culture enter the mainstream. The coming of age of the Ibiza scene and the proliferation of illegal raves had prompted the opening of commercial super clubs, and the charts were riddled with the big dancefloor hits of the previous summer.

But never mind Ibiza, Chicago or Radio 1’s Dance Show, Muggs is quite emphatic about where Fabric’s influences lie: “Fabric is London – Keith (Reilly, the other co-founder of Fabric) said the same. He was quite fanatical about the clubs he went to in the early 80s – the Beetroot, The Blitz – we think of them as dressy-up and New Romantic, but the music at those clubs was so advanced. They were playing all the latest proto-electro, Arthur Russell, Afro Disco… it was all really well mixed by interesting DJs. Keith was very emphatic that the London DJs then were as good as anything in New York.”

As interest in clubbing grew, and the scene leaked into Top of the Pops and tabloid showbiz columns, Reilly and Leslie decided to open a place that retained the nonconformist feel of the illegal suburban raves Reilly had organised in his native Essex. “Obviously American house became part of the mix, but Fabric was a reaction against Keith’s brother Billy running The Cross in New Cross, which was very feather boas, fluffy bras, [DJ] Seb Fontaine, showbizzy”.” Muggs says. “Keith wanted to keep it bohemian and underground.”

From the off, Fabric always celebrated the alternative, bringing the underground to a larger audience. Whether that was garage, dub techno, electroclash or tech house – or something in between – it always revolved around a central concept of challenging and delighting the audience. Because of that, it was an immediate hit. “In the first year, we got voted best in the world by one magazine,” Leslie tells me.

I proffer that the late 90s feels like one of the last time periods that you could experiment like that in the capital – by the 00s, former industrial spaces like Fabric were turned into executive apartments, rents were raised, complaints from gentrified neighbourhoods trickled in. “The reality is that Fabric and Home [a short-lived super club in Leicester Square] opened at the same time. Home collapsed, causing real issues for anyone looking to raise money for a nightclub. That caused problems for at least a decade – I heard a lot of stories about people trying to do different things but unable to get any institutional money.”

As someone who was only ever a punter, it doesn’t feel to me as if London has been very friendly to club culture, much to its detriment. Licencing laws, sound complaints, and stingy hours have worked to smother the late-night economy out of the city. “Through any time I’ve experienced, [London has] never ever celebrated the club culture in the way that Berlin or even… well I was going to say NYC, but they’ve been pretty hostile to their clubs,” replies Muggs. “It’s mostly part of a complete cultural failure among the mainstream to understand it, and that’s a double-edged sword, because it’s allowed that culture to develop its own characteristics, in the shadows, as it were.”

They finally came for Fabric in 2016. Two drug-related deaths led Islington Council to revoke the club’s licence, and forced it to close “permanently”. While the deaths were tragic, the immediate closure was perceived by some as an overly heavy penalty, and people rallied round to defend the club, among them London Mayor Sadiq Khan. As Leslie told The Guardian at the time: “Only eight months ago, a judge tested all our systems and said we’re a beacon of best practice.”

“That day when we did get shut down, I had this unbelievable feeling of clarity of purpose, of unbridled anger at the injustice of it,” recalls Leslie. “I came out of that 24 hours… I knew we were going to get it back, and I felt so utterly determined in terms of what our next mission was going to be.”

It wasn’t the last obstacle they would face. Despite Fabric reopening at the end of 2016, something more all-encompassing would come along little more than three years later. “Covid broke the cycle for a generation who didn’t get their first experiences of going out to a club every week,” says Muggs. Just as it did with most of us, however, it gave Fabric’s owners a chance to re-evaluate. “We were given these wonderful opportunities to make new relationships, which we weren’t necessarily looking for before because they were too outlandish – English National Opera, for instance,” Leslie tells me.

Fabric at the Opera brought drum and bass, ambient, acid house, techno, experimental dance and more to the London Coliseum in 2022. “We found common interests, as everyone’s audiences were disrupted. We [ended up doing] the first-ever contemporary live music event in St Paul’s last year,” Leslie says. The cathedral hosted RY X with The London Contemporary Orchestra in 2023, followed by an evening with Patti Smith this September.

But clubs are built on their legend. Favourite urban myths? “That I was in Craig David’s ‘Re-Rewind’ video,” Leslie immediately says, looking to set the record straight. “It was filmed in Room 3, and apparently I was dancing in the background of the video. That was something which was floating around for a long time. Yes, it was filmed in Room 3, but no, I wasn’t dancing in it.”

Muggs then half-remembers a Banksy anecdote, so I follow up with featured protagonist, Judy Griffith – Fabric’s programming director – a few days later. “We went to the launch of Trust No One by Banksy [an interpretation of the Justice Statue outside London’s Old Bailey], near the nightclub Turnmills,” she recalls. “Once the launch party was over, all of a sudden, these kids from the local estate came along. Before we knew it, they were taking the scales down and walking off down the street with them. We were shouting at them to stop but they just ignored us, so we chased them, and we got it back with no one harmed.”

“By now, it was too late to call the Banksy office, and we were drunk, so we decided to leave it at Fabric overnight… We woke up to the news that not only had the Banksy scales had been stolen, but that people from Fabric were suspects! We were supposed to be the heroes!”

Foiling opportunistic art thieves aside, in the end, it all comes down to the music – it’s what makes a venue persevere and thrive – which is why, when I ask Leslie what his favourite Fabric track is, his answer feels like a very good way for us to leave, once again, though those metal doors, blinking into the dawn. “Cpen: ‘Pirates Life’. It was on Craig Richards’s CD Fabric 01 – a really ethereal, floaty little song. I think Bill Brewster played it at the first birthday party, and I remember looking around thinking, ‘this is a magic place’.”

Here’s then to another quarter century of magic.

Fabric – the Book (White Rabbit) is out now. Prices range from £50 for the standard edition to £349 for the Deluxe White Rabbit Edition, published 17 December, available from the White Rabbit Store