A Complete Unknown’s account of Dylan’s crucial transitional period misses the most interesting thing about it

Bob Dylan is yet to see the new Bob Dylan biopic, A Complete Unknown. Despite this, our greatest contrarian, who recently joined X at the exact moment everybody else left, tweeted an excitable missive in which he called the film “fantastic”, while saying he was sure the actor he refers to as “Timmy” Chalamet would be “completely believable as me. Or a younger me. Or some other me.”

Sadly, though, that “other me” is considerably less interesting than the original one. A Complete Unknown, which reheats the story of how the former folk hero “went electric” in 1965, has received its share of five-star reviews and Oscar hype, with praise being showered upon star Timothée Chalamet. But the movie fails to do justice to reality, hammering its astonishing true story into the shape of a conventional music biopic, while being undone by a fatal flaw.

That flaw is this: you can only really understand what happened – or, indeed, care about it – by encountering the real Dylan. He was a mesmeric performer and a vocalist of extraordinary expression, who, like a great Shakespearean actor, unlocked the intricacies of his language for his audience. Chalamet is giving his best, but his best in this arena is completely pedestrian in comparison.

Stories of singular creative talent are simply better served by documentary. Luckily, in this instance, the heart-stopping footage of these epochal moments actually exists, contained in five immortal documentaries that allow you to experience a cultural revolution as it happened. And the tale told in those films, whether in piecemeal or in full, goes like this…

In 1963, a 22-year-old Minnesotan singer called Bob Dylan, who played acoustic music, was anointed the successor to left-wing activist-songwriters Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger, after giving voice to his generation’s social conscience on “protest” songs like “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “With God on Our Side”, anthems of the anti-war and Civil Rights movements.

The following year, as his work spiralled into abstraction, he served notice in “My Back Pages” that he had rejected earlier binaries, dismissing his “lies that life is black and white”, and asserting, “Ah, but I was so much older then/I’m younger than that now”.

In 1965, Dylan underscored his lyrical transformation with a musical one, using a rock band on his fifth album, and reviving the experiment at the Newport Folk Festival, where he played a short electric set shorn of political content, which was met with boos from former fans who accused him of abandoning his principles.

On cinema screens worldwide, moviegoers will see Dylan being pressurised not to play electric but defying the pleading and threats. The truth is more intriguing. He expected his audience to go along with him, and was startled and shaken by their reaction.

A friend found him alone at the after-party. “What happened?” Dylan asked him. “What went wrong?” It was only when he was booed again at Forest Hills in New York a month later that he embraced the conflict.

A subsequent trip around America and Europe proved to be less a concert tour and more a succession of pitched battles with disgruntled folkies. The most symbolic was at Manchester’s Free Trade Hall, where a spectator’s cry of “Judas!” prompted a furious rebuttal from Dylan, his blistering full-band version of “Like a Rolling Stone” hinging on the sneered question, “How does it feel to be on your own?”.

The consensus now – as it was then outside the small bubble of the folk world – is that Dylan was right. He was, in his later phrase, “a musical expeditionary”, whose duty was to his art.

To give full flight to his genius, he had to shed the shackles of dogma. Under this telling, his first top 10 hit, “Rolling Stone” – released in July 1965, five days before Newport – was the sound of rock music spreading its wings, after which anything was possible. It’s a compelling narrative, and probably largely correct, but it isn’t the whole picture.

Dylan’s earlier songs had been every bit as remarkable, just in a different vein, and steeled by seductive collective certainties. To many who had believed in him, he had then turned from a writer with a social conscience into a millionaire speed-freak who didn’t care about Civil Rights any more.

And while it’s impossible to decry an act of creative metamorphosis that ultimately gave us “Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands”, “Abandoned Love” and “Every Grain of Sand”, there were things lost as well as gained: yes, that incomparable folk-era sound, but also friendships, innocence, and the struggle for a certain type of world. The great Dylan documentaries, whether wittingly or otherwise, do battle over that narrative.

The definitive film, provided you keep your wits about you, is No Direction Home (2005), assembled by Martin Scorsese from archive footage, and interviews conducted by Dylan’s manager. Culminating with the ’66 tour, it’s the legend writ large: an exhilarating ride that frames those climactic confrontations as Dylan’s artistic apotheosis.

His retrospective justifications can seem disingenuous. Positioning himself purely as a musician, he says: “For some reason, the press thought that performers had the answers to all these problems in society … I mean, it’s kind of absurd.” To which the answer is surely, “Bob, you wrote ‘Only a Pawn in Their Game’.” Yet Scorsese shows affectingly how the extreme pressure of unwanted expectations left Dylan desperate to escape.

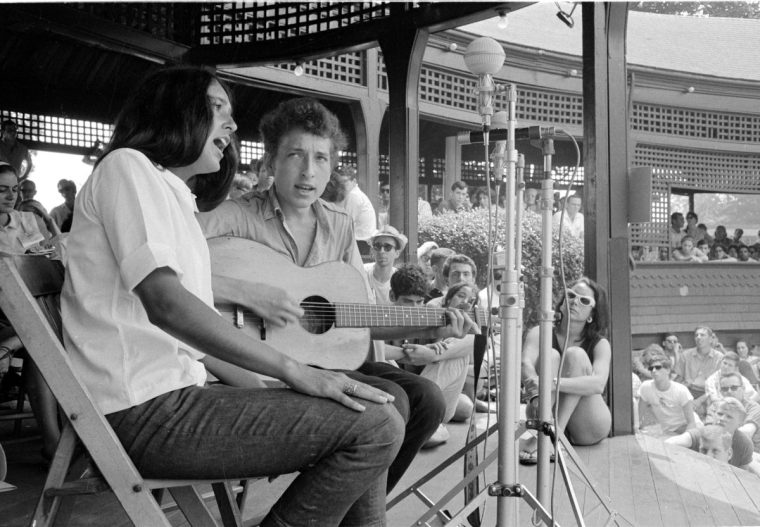

Despite such sympathy, the film is no hagiography. While omitting his drug use and declining to ask ex-girlfriend Suze Rotolo to revive her assessment that he was “a lying shit of a guy with women”, it engages with folkies’ feelings of betrayal. Joan Baez had envisaged the two of them spearheading a movement for progressive change. Dylan told her he just wanted to do his music. “And yeah, I was disappointed,” she says.

On the other hand, have you heard the music? DA Pennebaker’s footage of Dylan on stage in ’66 has a different energy to anything else you’ve ever experienced: a sulkily beseeching “Mr Tambourine Man” from the acoustic first half, a mesmerising “Ballad of a Thin Man” from the second, with Dylan at the piano, one hand writhing towards the heavens amid the cacophony.

Scorsese also employs material shot by Murray Lerner for the film Festival!, which was filmed across four iterations of Newport from 1963 to 1966, and released the following year. Lerner was awestruck that, via electricity, Dylan had “reached a mass audience with poetry”, but his own movies capturing the transformation play as tragedy. The chaotic but dazzling Festival!, which includes Dylan among its cast of dozens, evokes the idealistic communitarian vision of Newport that his act of vandalism ultimately destroyed.

Another of Lerner’s films, The Other Side of the Mirror (2007), achieves a profound poignancy simply by showing his appearances at Newport in order. In ’63, he’s a scrawny, deferential kid holding the elders spellbound with an epic about iron-ore mines. The next year, he’s a superstar with an aww-shucks persona, unwisely introduced with the notorious words: “You know him, he’s yours.” And then comes ’65, a skittish Bob pulling on a leather jacket and a Stratocaster, and unleashing hell with “Maggie’s Farm”, his abbreviated delivery duelling with Mike Bloomfield’s spitting guitar.

Not every folkie hated it. Paul Nelson, from Sing Out! magazine, wrote: “I choose Dylan. I choose art.” Many, though, were bereft. “He had so much promise,” Seeger lamented, questioning whether the hopes he’d pinned on the kid had led to music that “now held no hope”. Producer Joe Boyd encapsulated the sense of loss: “The old guard hung their heads in defeat while the young, far from being triumphant, were chastened. They realised that in their victory lay the death of something wonderful.”

Seen through that prism, the footage from ’63 of Dylan singing “Blowin’ in the Wind” with Seeger, Baez, and the Freedom Singers – four Black Civil Rights activists – is almost unbearably moving. He is Seeger’s great hope, he will be one of Baez’s great loves, he has given this anthem to the struggle. But he’s not what they think he is, and within two years, ending on this very stage, he is going to betray them.

Others, meanwhile, mourned their rapport with the artist, artificial though it may have been. “The kids were calling out for him to do the songs that meant something to them,” Baez recalled of their joint tour in early 1965. “They were reaching out to him, and he didn’t care.”

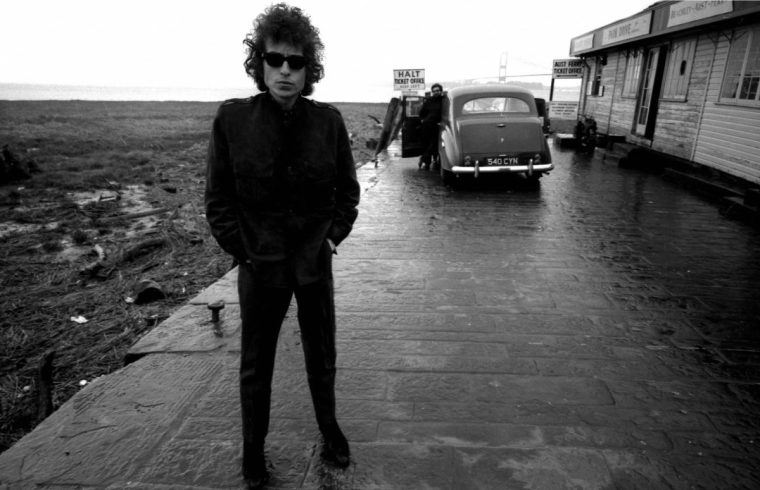

That was his brat spring, and Pennebaker covers the next chunk of it in the landmark, inkily photographed ob-doc, Dont Look Back [sic] (released two years later), which follows Dylan on tour in the UK. Hip, flip and arrogant, he’s a spoilt kid channelling something he doesn’t quite understand, reaching new realms of expression in fragments of astonishing performance footage. But while genius beguiles, his cynicism and surreal humour are also a breath of cool air next to the worthiness of Newport.

Dylan is still a singer with a message, only now the message is about himself, the songs sharing the open secret that “everything passes, everything changes, just do what you think you should do”. In 65 Revisited (2007), assembled from outtakes, Dylan watches John Mayall and Eric Clapton’s thunderous Bluesbreakers on TV, and an idea forms that he could perform “Maggie’s Farm” the same deafening way. Two months later, he did.

While the folkies’ response is often ridiculed, for them the stakes were stratospheric. They believed in the power of art to effect social change, so when Dylan turned away from polemical songs, drowning his words in electrical noise, he wasn’t merely switching genre, he was abandoning progressivism, in the year of the Watts Riots and the Gulf of Tonkin.

But as he puts it, with stylised rebelliousness, in No Direction Home: “They were tryna make me an insider to some kinda trip they were on – I don’t think so.” By betraying the folk movement, he stayed true to himself; in accentuating individual autonomy, he killed one dream of the 60s in order to birth the other.

A Complete Unknown struggles to articulate that central tension, barely engaging with Dylan’s crucial transitional period, so that we comprehend only what he’s fleeing, not what he’s fighting for. The theme becomes escape, not self-realisation. While a movie like this must, by definition, be a little faithless to the facts, its compressions, inventions and inversions actually make the story less interesting.

It’s probable that the more you like Dylan, the less you’ll like the film. The hope, though, is that it serves a different function, providing a gateway to the genuine article and introducing a new generation to some of the most electrifying music ever put on record – or on film.

‘A Complete Unknown’ is in cinemas now. ‘No Direction Home’ is on BBC iPlayer