Image copyright

Image copyright

Family photo

Gemma and her mother, Helen

When Gemma Nuttall developed cancer, her family raised thousands of pounds online, with the support of actress Kate Winslet, to send her to a German clinic. But there was no happy ending – and fears remain that crowdfunding puts new pressure on vulnerable families.

Doctors saw the first signs of Gemma Nuttall’s tumour when she went for a pregnancy scan.

Everyone thought it was nothing at first – a cyst or a glitch in the monitor.

But a month later she was told it was ovarian cancer.

Gemma decided to delay chemotherapy until her daughter Penelope was born – and for a while life returned to normal.

Then the headaches started.

The cancer had spread to her brain and in spring 2017 she was offered palliative care and given months to live.

Image copyright

Family photo

Gemma with her daughter Penelope

“I just thought, ‘Well, that’s not happening. I’m not losing her. She’s 28 years old with a baby of her own. I need to do something,'” Gemma’s mother, Helen Sproates, told the BBC’s Victoria Derbyshire programme.

“That’s when I started looking at alternative treatment abroad. I jumped on the internet and started searching.”

Helen found a clinic in Germany, the Hallwang, that offers alternative therapies such as ozone treatment and vitamin infusions alongside drugs not available on the NHS.

The clinic does not publish survival rates but its website includes testimonies from former patients treated there with apparent success.

It was one of these testimonies that caught Helen’s eye.

Image copyright

Family photo

Gemma developed ovarian cancer, which spread to other parts of her body

But the decision to take Gemma to the Hallwang brought a bigger pressure. The bill for just one trip was €108,000 (£93,000), with future visits needed for “top up” treatments.

“It was like getting hit by a sledgehammer,” Helen said. And the process of deciding what to do and how to do it had been “horrendous”.

Helen said: “You have to really sit down as a family and say, ‘If we do this, if we end up destitute with nothing and it doesn’t work, where are we going to be?’

“You have to decide what you are going to do about it. And then you have to live with the consequences.”

Raised hopes

Solid figures do not exist but, anecdotally, charities and doctors have no doubt that the number of cancer patients heading overseas is rising rapidly.

Information about options is now just a click away online, though it may not always be accurate or reliable.

Heavily publicised cases, such as those of Ashya King, have raised hopes and encouraged others.

Treatments are often very expensive but thanks to the internet and social media they have become affordable – for some.

More than £20m a year is now being raised on crowdfunding sites for cancer treatment not available on the NHS, new research from the Victoria Derbyshire programme suggests.

If a crowdfunding campaign takes off, it can raise tens of thousands of pounds in days.

Critics fear this could be exploited by clinics, some of which charge hundreds of thousands of pounds for treatment.

Gemma’s family took out loans and sold a house to get to the Hallwang.

Image copyright

Family photo

Gemma’s family spent thousands on treatment for her at the Hallwang

But it wasn’t nearly enough. So they turned to the internet.

The Victoria Derbyshire programme’s analysis of the three main websites used for crowdfunding cancer therapies shows more than £20m was raised in the year to February 2019 for treatment not available on the NHS.

This sum does not include millions donated directly into patients’ bank accounts.

While some people are able to raise fortunes, countless others struggle to do so.

Success depends on many factors, including the fundraisers’ personal connections, the physical appearance of the patient – young women and children tend to raise more than the middle-aged or elderly – and the amount of effort put into keeping donors informed and engaged.

Many families who have gone down this route say they found it onerous and invasive.

Helen says crowdfunding took a lot out of the family

Helen’s decision to go public and crowdfund led to “quite big rows” with her daughter.

“We are a private family. Gemma was quite shy and didn’t want to get involved with any of it and nor did I to be honest,” she said.

“But we needed a high profile to get more funds to get her to Germany.”

Cancer charities say they are increasingly concerned about photographs and video clips of young children, often very sick in hospital, being posted online to solicit donations.

And at a time when a parent most wants to spend time with their child, they have to focus on fundraising instead.

Sarah Lindsell says for some families crowdfunding feels like an “obligation”

Sarah Lindsell, head of the Brain Tumour Charity, told BBC News: “I really feel for families at that stage where they might just want to be sitting on the sofa cuddling or reading a story and at the same time they’ve got Facebook open because they’ve got 100 replies they’ve got to give.

“For some families, it’s starting to feels like an obligation, ‘If you haven’t tried this, are you a good parent?’

“That’s a very, very difficult position to be in.”

Some relatives say their families have been ripped apart by the pressure of trying to meet rising bills.

The parents of one young child with terminal cancer told BBC News they had deliberately made the decision not to raise money for treatment overseas but to “make memories” with their daughter instead.

But they had been constantly harried by other family members to reverse the decision.

Celebrity involvement

Gemma’s crowdfunding campaign raised £16,000 – a large sum but still nowhere near enough for a first round of treatment.

Then, out of the blue, an email arrived. Helen thought it was fake at first. It was from someone saying they worked for Kate Winslet.

The actress, who had read Gemma’s story, wanted to help.

Winslet raised money herself and media coverage boosted the wider crowdfunding campaign.

“I’m so unbelievably grateful,” Helen said. “We were very, very, very lucky.”

Thanks to Winslet, Gemma was able to make seven trips to the Hallwang.

Image copyright

Getty Images

Kate Winslet brought great awareness to Gemma’s story

Germany has quietly emerged as the centre of Europe’s private cancer industry, with dozens of clinics offering very different treatments.

The Hallwang is by far the most high profile, catering to British patients as well as others from the US, Australia and the Middle East.

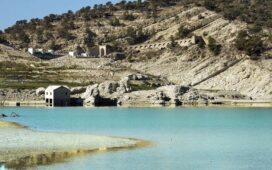

From the outside, the clinic, in the Black Forest, looks more like a giant Alpine chalet, with gardens and its own restaurant.

The Hallwang’s largest shareholder, Albert Schmierer, owns a chain of nearby pharmacies specialising in homeopathy, a controversial treatment that the NHS stopped funding in 2017.

The Hallwang offers medical treatments not routinely available on the NHS

Costs are high.

One father told BBC News he had been charged £600 per night for overnight stays with his sick child – on top of charges for his son’s own bed.

Paracetamol tablets had been charged at 12 euros (£10) for two, he added.

The clinic claims it has a specialist cancer doctor for every two to three patients and a nurse to patient ratio of “nearly 1:1”.

It offers patients alternative or “complementary” therapies, though it says this is a small part of its work, alongside medical treatments not always available on the NHS.

Immunotherapy is a relatively new type of medicine that uses the body’s own immune system to destroy tumour cells.

Results for skin and blood cancers have been encouraging in some, though by no means all, cases.

However, for many solid tumours – such as ovarian or brain cancer – the science is at an early stage, the benefits are even less clear and no treatment is close to approval for NHS use.

Image copyright

Family photo

Gemma was treated seven times at the Hallwang

Testimonies from a number of patients suggest the Hallwang has exaggerated the likely effectiveness of these drugs, with one woman with stage-four pancreatic cancer apparently being told remission lasting five years was a possibility.

Pancreatic cancer experts in the UK told BBC News in their opinion the patient, who died within the average time predicted by the NHS, had been given false hope.

The Hallwang had also advised a patient with terminal brain cancer the treatment could prolong her life by up to 10 years, her husband said.

‘Extraordinary’ results

Alongside immunotherapy, patients like Gemma are sold a variety of poorly explained cancer vaccines, designed to train the body to better recognise tumour cells.

One family told BBC News they had been charged £45,000 for a series of five vaccine injections developed by analysing an individual tumour.

Patients and their NHS doctors said they had been told little more about the vaccines, apparently developed at the clinic itself, despite repeated inquiries.

The Hallwang did not answer the BBC’s questions about the vaccines’ content.

The clinic did say it is one of the “pioneers in the field of personalised and precision-based oncology” and has a “clear focus on evidence-based treatment” which has achieved, for some of its patients, “extraordinary long-term… results.”

It said standard care often increases overall life expectancy in cancer patients by only a couple of months.

Image copyright

Family photo

Gemma and Helen

“If [our] patients survive with our treatment strategies one, two or three years longer, this is a real breakthrough,” it said.

“Especially given the improved fitness and quality of life patients experience at our clinic.”

The Hallwang can cite anecdotal evidence of patients who have survived longer than NHS prognoses, which are rough estimates based on average survival rates.

And the BBC has spoken to one British patient diagnosed with terminal skin cancer five years ago who is convinced the clinic saved his life.

But there is no way to tell whether the Hallwang extends or improves most of its patients’ lives – because it does not publish outcome data.

BBC News repeatedly requested access to its results so that these could be compared with outcomes for patients on NHS palliative care but did not receive a response.

Instead, the clinic directed us to its Facebook page.

“Life-saving treatment”

Doctors at the Hallwang insist they are honest with patients and “always [have their] best interests at heart.”

“We never talk about ‘cure’, nor do we use phrases like ‘beat it’, ‘make it’, ‘kick it’, et cetera. Our medical team consists of medical oncologists, not sports commentators,” the clinic said in a statement.

However, in a marketing video on the front page of the clinic’s own website, a patient can clearly be heard saying he had been told the medical team would “try and beat my cancer”.

Other families told BBC News phrases such as “full remission” had been used.

Recalling conversations about her daughter’s prognosis, Helen said: “100% we thought she was going to get cured and get in remission and there was going to be a miracle.”

Gemma made seven visits to Germany in total, in 2017 and early 2018, paying on average about £60,000 for each round of treatment.

And for a while, it appeared to be working.

Image copyright

Family photo

Gemma was travelling abroad for treatment every three weeks

Scans at the Christie NHS cancer hospital, in Manchester, in June and October 2017 showed no sign of tumours in Gemma’s body.

And in February 2018, she appeared on national television alongside Kate Winslet to thank the actress for “saving her life”.

But by this time the strain of travelling abroad every three weeks was taking its toll and Gemma wanted a break.

The Hallwang advised her to keep returning for “maintenance” treatments, costing £20,000 less than she had been paying before. But the money was beginning to run out.

And Helen had to choose between paying for continuing treatment or saving the remaining money in case the cancer returned.

“It’s like spinning plates,” she said.

“If I stop doing it, are they going to smash to the ground or stay up there?

“I beat myself up now as to whether I made the right decision.”

They decided to stop the treatment.

Gemma ‘inspired’ others

In May 2018, a year after her first round of immunotherapy, Gemma started complaining of back pain.

A scan confirmed the worst – the cancer was back and had spread to her spine.

Returning to Germany was never an option as she became too ill to travel. She died last October.

A video of Gemma on television talking about how her life had been saved by Kate Winslet’s donation remains on the Hallwang’s website.

Gemma’s testimony remains on the Hallwang website

Helen wants it taken down, along with testimonies from other patients who have died.

“They are not here anymore, so to use them to get more people to go is absolutely wrong,” she said.

The person who initially inspired her to take Gemma to the Hallwang “is not turning out well”, she said.

“And that’s what happened with Gemma. She’s inspired a lot of people. But Gemma hasn’t turned out well,” Helen said.

Helen believes the Hallwang did extend Gemma’s life – but she cannot say with certainty that going there was the right decision.

Image copyright

Family photo

Gemma with daughter Penelope

“You do not do anything else except get on the plane, go have treatment, come back on the plane,” she said.

“That’s it. That’s your life – no holidays, no family time, barbecues, no happy times.”

Gemma’s daughter, Penelope, is now living with her father.

“I ask myself should we have done the bucket list and spent the last few months of Gemma’s life with her daughter, trying to be happy and make memories?

“But it is what it is, it’s done now.”

Follow the BBC’s Victoria Derbyshire programme on Facebook and Twitter – and see more of our stories here.